|

This wonderful book is an extraordinary rarity among

early American imprints. It is the first job

undertaken by Benjamin Franklin as proprietor of his own

print shop in Philadelphia. Franklin's hard work

printing the book, immortalized in his own account of

the printing in his autobiography, is what built his

reputation and launched his business.

At just 22 years old,

young Benjamin Franklin parted ways with Samuel Keimer,

his first boss in the printing trade in Philadelphia, to

start his own printing business. Franklin and

Keimer had a stormy relationship, with the younger

Franklin always confident that he could do a better job

than the older Keimer. Their story is the

quintessential American entrepreneur story, and this

book bore witness to that episode. Keimer was

commissioned by the Quakers to print the work beginning

in 1725, but by 1728 he had not yet finished. The

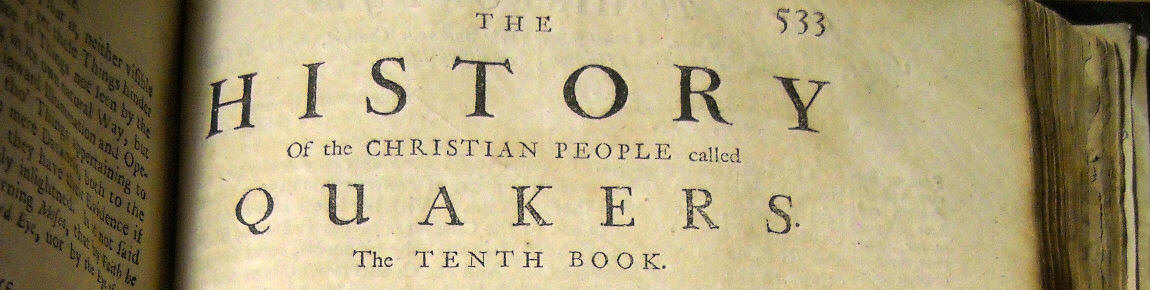

book, The History of the Rise, Increase, and

Progress, of the Christian People Called Quakers,

written by William Sewel, was first published in the

Dutch language in Amsterdam in 1717, with a second

edition published in English in London in 1722. In

1725, the Quakers desired an American edition and they

approached Samuel Keimer to do the job. Franklin

likely worked on the book occasionally while he was employed as Keimer's foreman, but in 1728 Franklin and associate

Hugh Meredith, who also worked in Keimer's shop,

established their own print shop with a press and

type sets that Franklin procured from London. Although

Franklin's name is not on the title-page, Franklin and

Meredith actually printed 44 folio sheets, which were

divided into 176 individual pages of the book, beginning

with the Tenth Book on page 533. The book had a total of

710 pages, in large folio format; only the second book

of this size to be printed in the colonies up to that

time.

Franklin himself writes in his own autobiography

specifically about the job of printing this book.

He first describes The Junto, the club that Franklin

organized among friends for discussing important matters

of the day. After briefly introducing the members

of the club, he mentions how they were helpful in

getting him started in his printing business.

Joseph Breintnal, one of Franklin's friends, helped

arrange this first job.

|

"Breintnal particularly procur'd us from the

Quakers the printing forty sheets of their

history, the rest being to be done by Keimer;

and upon this we work'd exceedingly hard,

for the price was low. It was a folio, pro

patria size, in pica, with long primer

notes. I compos'd of it a sheet a day, and

Meredith worked it off at press; it was

often eleven at night, and sometimes later,

before I had finished my distribution for

the next day's work, for the little jobbs

sent in by our other friends now and then

put us back. But so determin'd I was to

continue doing a sheet a day of the folio,

that one night, when, having impos'd my

forms, I thought my day's work over, one of

them by accident was broken, and two pages

reduced to pi, I immediately distributed and

compos'd it over again before I went to bed;

and this industry, visible to our neighbors,

began to give us character and credit;

particularly, I was told, that mention being

made of the new printing-office at the

merchants' Every-night club, the general

opinion was that it must fail, there being

already two printers in the place, Keimer

and Bradford; but Dr. Baird (whom you and I

saw many years after at his native place,

St. Andrew's in Scotland) gave a contrary

opinion: "For the industry of that

Franklin," says he, "is superior to any

thing I ever saw of the kind; I see him

still at work when I go home from club, and

he is at work again before his neighbors are

out of bed."

- Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography |

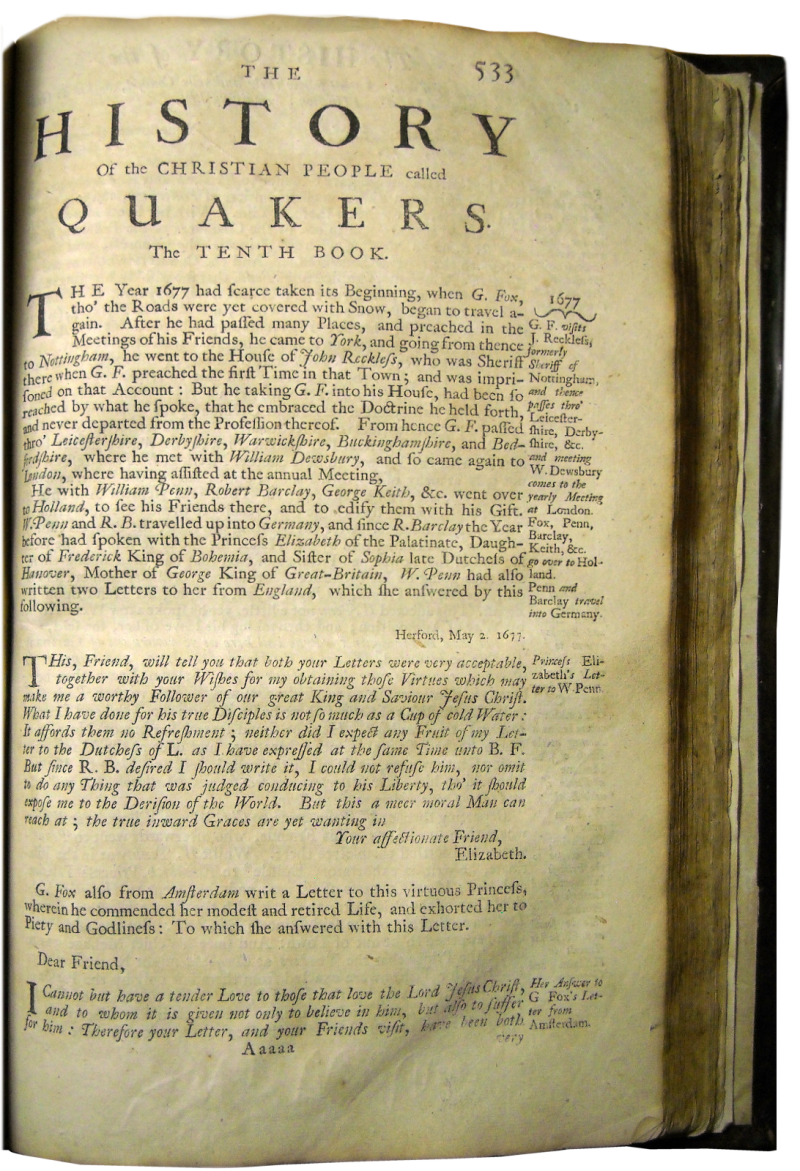

This is the book,

and these are the pages, that Benjamin

Franklin was working on during those long

days and late nights. It is also

interesting to compare the composition and

inking of the types of the book,

before page 533, printed by Keimer, to Benjamin Franklin's compositing

and printing. Franklin's skill level far exceeded Keimer's; and Franklin was using new types that he

had just received from London, while Keimer's types

are old and worn. Pages 533 to the end are the work

of a young Franklin who is already a master of his

craft. The book is printed on American and foreign

paper. These pages have some of the earliest

American paper watermarks from the earliest American

paper mills. The main printer in Philadelphia,

Andrew Bradford, prevented Franklin from procuring

paper from the well-established Rittenhouse Paper

Mill, so Franklin was left to his own resources to

try and find suitable paper for the work. The newly

established Gorgas Paper Mill just outside of

Philadelphia was an early source for Franklin's

paper. This book has watermarks from that mill.

The pages are clean and without tears, overall in

very good condition. The book is missing the

dedication page, two other leaves in the text, and

the last three index leaves printed by Franklin.

(The copy held by the American Antiquarian Society

is missing five leaves and the copy held by the

Library of Congress is missing one leaf of the

index.) There has been professional archival repairs

to the fore-edge margins of the first four leaves.

The book has been skillfully rebound in the original

style of William Davies, the original binder of this

work. It is bound in the identical full-calf,

exactly duplicating the original English panel style

decoration, down to the corner fleurons that were

made especially for this restoration. There

were a total of only 500 of these books printed, and

likely that very few copies have

survived. Most examples are institutional collections.

In C. William Miller's

Benjamin Franklin's Philadelphia Printing,

1728 to 1766, a comprehensive survey of imprints

produced by Benjamin Franklin during his career as a

printer, this

publication is the first, with a survey number of

Miller 1. |

|

The first page of the section printed by

Benjamin Franklin and Hugh Meredith. |

|

|

|