The

ways by which stars are added to the

canton of a flag are very varied,

and the different techniques

employed are often good indictors

that help to determine a flag's date

and usage. Here we explore the

various techniques and terminology

related to the application of stars

to an American flag.

Methods for applying stars that I am

familiar with are: sewing, painting,

printing, clamp-dying, gluing,

stamping, embroidering, crocheting,

affixing and reverse-appliqué.

There may be other methods, and I

encourage other collectors to share

their experiences with other

techniques. The effect of each

technique leaves a distinct

character on the flags themselves,

and is an important aspect in the

great variability of American flags.

Sewn Stars

Of

the methods for applying stars by

sewing them to a flag, the two

predominant methods are

single-appliqué and double-appliqué.

On single-appliqué flags, the maker

cuts a hole in the blue canton in

the shape of a star and uses a

single piece of white fabric to

create the star. Although the

term "single-appliqué" is commonly

used to describe this "cut through"

approach, it would also accurately

describe flags with stars only sewn

to one side of the canton. On

double-appliqué flags, the maker

cuts two white stars and stitches

them back-to-back, one on each side

of the canton.

|

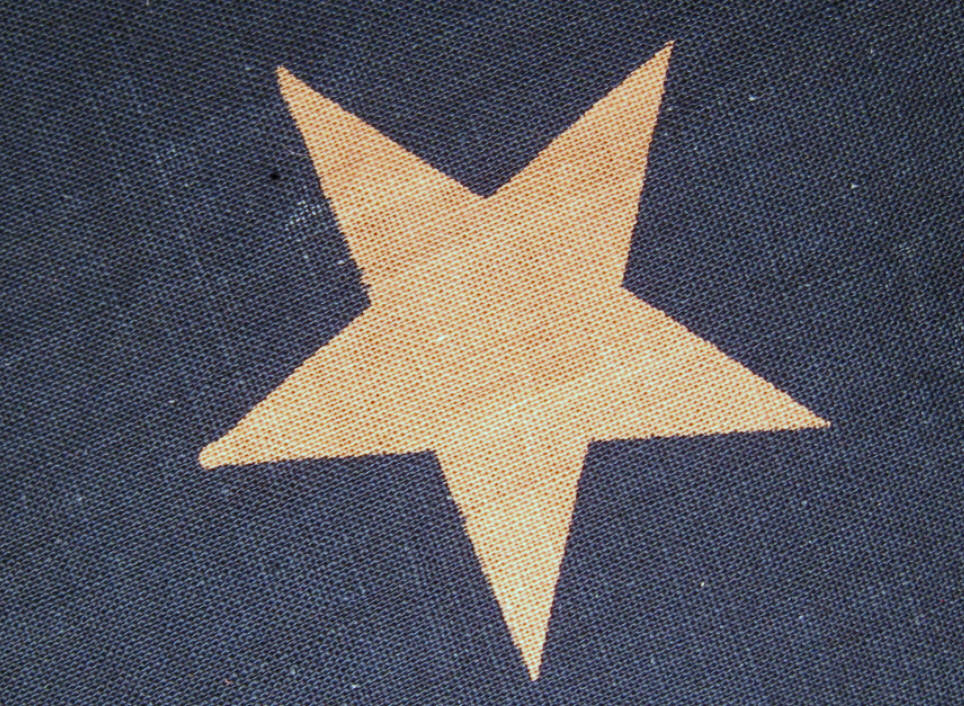

Single Appliqué

|

Technique: Sewn,

Single-Appliqué. This

photo shows beautiful

single-appliqué work on a

magnificent 4-5-4 pattern

maritime flag made in

Boston, circa 1870, by the

firm of Leighton and

Pollard. The entire

flag is hand-sewn. |

|

|

Double Appliqué

|

Technique: Sewn,

Double-Appliqué. The

stars on this late period 13

star ensign are sewn onto

both sides of the canton,

back to back. The use

of a zig-zag stitch that

crosses the center of the

star indicates that the flag

is most likely not earlier

than 1892 when the zig-zag

stitch technique for

applying stars was patented. |

|

Painted Stars

Painting is an obvious choice for

applying stars to a flag, yet

painted flags are somewhat scarce.

The reason is most likely because

flags, being made from fabric, have

always been sewn by seamstresses who

most likely find it natural to

simply sew fabric stars, rather than

switching to another medium.

There are some cases, however, where

painting stars makes sense, and each

case is shown here. One case

is where painting allows easier

production of complex designs.

A second case is the use of gilt

paint on silk flags, a technique

typically reserved for military

flags where strong, light, silk is

better suited to weathering harsh

battlefield conditions than other

materials such as cotton, where the

flags are lighter than wool flags

when carried on horseback, and where

the integrity of the silk,

un-punctured by sewn stars, most

likely resulted in less tearing and

breakdown. A third case is

where materials are scarce or the

flag is made hastily from readily

available materials, one of which is

paint. A fourth case is where

specialized paints increase the

lifespan of the flag and afford it

certain properties, such as a higher

degree of reflectivity and a

protection against discoloration

with age.

Printing

Printing stars is actually a

misnomer. In fact, in most

cases, the stars are not printed,

but rather the blue canton around

the stars, and the stars themselves

remain the color of the base fabric

of the flag. Printed parade

flags most commonly fall into this

category.

|

Technique: Printed.

This is a close up view of

the canton of the

Andersonville Prison

flag. This is a good

view of a printed parade

flag that is solidly

attributed to the the period

of the Civil War.

|

|

Clamp Dyeing

The

process for clamp dyeing involves

clamping the fabric of the flag such

that the shape of the stars is

clamped and does not take on dye.

The process dates to the mid-19th

century. Once the section of

the flag which is clamped is dyed

and dries, the clamps are removed

and the stars remain the color of

the base fabric. In theory

this could be a process that could

scale to mass production and produce

large flags without the need for

sewing stars (unlike the process of

printing, which becomes cumbersome

the larger the flag). In

practice, bleeding of the dye into

the star region resulted in a

perception of manufacturing defects,

therefore making the process less

commercially successful than hoped.

|

Technique: Clamp Dyeing.

Close examination of this

star shows some of the

irregularities introduced by

clamp dying, such as the

stubby tip of one of the

star points and some minor

bleeding of the blue into

the white area of the star.

This unusual flag features

54 stars and dates to the

early 20th century. |

|

Stamping

Although it's debatable whether

stamping is simply another method of

applying painted stars, I include it

as a separate category simply

because it is a variation of a

technique to apply the stars.

A stamp in the shape of a star might

be fashioned from wood, metal,

rubber, or another material, and

then dipped into paint and pressed

onto the flag. This differs

from actual painting where a brush

is used to apply the paint, and

close inspection of some painted

flags shows evidence of stamping as

the technique for applying the

paint.

|

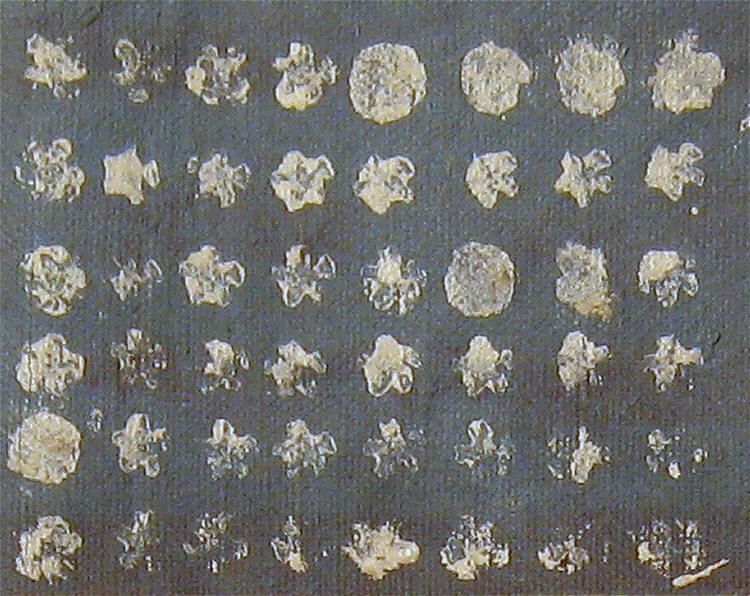

Technique: Stamping.

This close up view of a

Liberation Flag made in

Calais, France in 1944 to

welcome American soldiers

shows evidence of stamped

stars. The stars are

very small, but are of

uniform size. The

paint's application is

uneven and areas of thick

paint on the edges of some

stars, as well as the

circular imprint of other

stars, leads me to believe

that the person making the

flag probably carved the

shape of a star onto the tip

of a wooden dowel, and used

the dowel to dip into paint

and stamp the stars onto the

painted canton. |

|

Embroidering

Embroidered stars are made by

building up individual stitches of

thread to form the star.

Embroidery is often done by hand,

but by the late 19th century and

through the modern day, machine

embroidery is used to apply stars

that are very regular in size and

shape. Hand embroidered stars

on flags that date to the early 19th

century are known to exist.

|

Technique: Embroidered.

These crude embroidered

stars on this Civil War era

homemade parade flag are

intricate, yet minute.

The entire flag is just 2.5

inches square, and the

canton just 1.5 inches

square. Yet the flag

features the entire

complement of 34 stars.

The stripes of the flag are

also embroidered. |

|

|

Technique:

Embroidered. Here the

entire body of the star is

embroidered. This flag

of 46 stars, circa 1910, is

made of silk and was

produced as a military stand

of colors. |

|

|

|

Technique: Embroidered.

The stars of this hand sewn

homemade 45 star

flag, circa 1900, are hand

embroidered, with the

embroidery covering a base

in order to build up and

define the shape of the

star. |

|

|

|

Technique: Embroidered

stitching. The stars

of this superb homemade flag

from the American Centennial

are made of cut silk, but

rather than being sewn to

the canton with a simple

stitch, the seamstress, Ms.

A. Whipple of Albany, New

York, embroidered the

borders of the stars to

affix them to the canton. |

|

Crocheting

Crocheting or knitting is yet

another way to form stars, usually

employed on homemade flags that date

from the early 20th century to the

modern day. Crochet stars are

often folky and very intricate,

especially when made for the cantons

of smaller flags.

Affixing

Stars that are affixed to a flag are

usually made of a material that is

difficult or impossible to stitch

into without causing damage or

undesired effects. The stars

might be made of metallic foil,

plastic or other materials.

|

Technique: Affixing.

On this Confederate Bible

Flag, fifteen gilt foil

stars are affixed using a

star-shaped cross stitch

across their centers.

The gilt foil is similar to

the material found inside

the cases of Civil War era

photographs. |

|

Reverse-Appliqué

Reverse-appliquéd construction

involves cutting through the shape

of stars on the canton and sewing

the canton to a single piece of

white fabric, which serves as the

flag. On some reverse-appliqued

flags, the canton is cut and sewn to

both sides of the flag, allowing the

white fabric to show through,

forming stars on both sides.

This technique is very rare and

usually leads to flags with a very

folky appearance.

|

|

Technique:

Reverse-Appliqué. This

fantastic flag of the Civil

War period features 35

reverse-appliqué stars on

both sides of the canton, made by

cutting through pieces of

calico dress fabric.

The red stripes are also

appliquéd to the flag on

both sides. The flag

was hung from the Olive

Green General Store in Olive

Green, Ohio on the border of

Ohio and West Virginia.

The three holes across the

flag are bullet holes shot

through by Southern

sympathizers who fired on the

flag as it hung over

the general store,

enduring evidence of tensions within

the region over West

Virginia's secession from

Confederate Virginia.

|

|

Gluing

Cut stars glued

to the canton are a common way of affixing stars

onto flags made at home or by school children.

|

|

Next:

Great Star Flags |

|